Review Communism and Zionism in Palestine During the British Mandate Shira Robinson

T he global conversation about race and racial oppression in recent years, which has reached new levels of visibility since the summertime of 2020, has emerged largely every bit a reaction to police violence in the United States and the piece of work of the Movement for Black Lives coalition.

A woman takes pictures of her friend in front of the Israeli separation wall with a landscape depicting Iyad al-Halaq, an unarmed Palestinian who was shot dead by Israeli law and referenceing George Floyd who was killed past police in the U.s. in May 2020. Bethlehem, West Bank. Mussa Qawasma/Reuters

Its global reverberations have often been distinct, even so. Activists are not only making connections between Usa practices and patterns of racial oppression and those in their own countries; they are also highlighting features of racial violence that are unique to different contexts.

Some of the almost resonant reverberations have emerged at the nexus between the Move for Blackness Lives and the Palestinian struggle, through links that can exist traced back to the summer of 2014. The constabulary killing of 18-year-quondam Michael Dark-brown in Ferguson, Missouri, the wave of protests beyond the United States which ensued and the harsh, military-similar response of law enforcement to the protests in Ferguson in particular, coincided with Israel'southward Functioning Protective Shield offensive that devastated the Gaza Strip. Against this properties, activists in Palestine and in the The states increasingly began invoking each other'due south struggles.

This moving ridge of solidarity, focused at first on Gaza and Ferguson, publicly reinvigorated a host of ongoing and deep historical ties between Black American and Palestinian struggles against oppression.[1] Scholars typically focus on the North American-Middle Eastern nexus of these connections, particularly equally it crystalized in the 1960s around the ascension of the Blackness Power movement in the United States and the Palestinian Liberation movements in the Middle East. All the same, many of them rightly note that these connections were also embedded in larger geographic contexts—encompassing much of the Global South—and had longer histories, dating to the belatedly nineteenth century.

Considering these broader contexts brings to the fore the crucial role of empire equally a historical, political and social formation, on the i hand, and divisions of labor, on the other, in shaping both racialization and ideas nigh racial belonging and solidarity in twentieth-century Israel and Palestine. That is to say, how race operated every bit a category was a function both of local developments—outset and foremost, Zionist colonization and British rule—and of a world historical process that witnessed the emergence of the global color line—the idea that race and racism defined global divisions of ability. The Black American sociologist Due west.Eastward.B. Du Bois in 1903 defined the global color line as "the problem of the twentieth century," a problem that has endured into the twenty-first century.[2] Charting how the color line unfolded and how race was deployed historically in Palestine and State of israel, sheds lite both on the extent of its spread and on what has enabled its durability as a global structure.

Lineages

The global scale of racial politics does not forbid the importance of local contexts. In Palestine and State of israel, this context was starting time and foremost the colonial human relationship between Zionist settlers and Palestinians, and to varying degrees also Middle Eastern and North African Jews (henceforth, Mizrahi Jews), which began taking shape during the final decades of the Ottoman Empire. The formation of this colonial relationship was then accelerated and compounded past the institution of the British mandate for Palestine subsequently Earth War I. And yet the context of the global color line, of a world ordered along racial lines, even so informed how this colonial relationship was opposed by Palestinians and Mizrahi Jews, and how it was understood—even so reluctantly—past many Zionists.

Britain's empire played a pivotal function in shaping the contours of the global color line and impelled local actors to engage with and position themselves along it. All the same, ethnic Palestinians and their Zionist settler counterparts as well drew upon independent reservoirs of racial idea.

Britain's empire, which brought together a Kiplingesque notion of the "white man's burden" and elaborate racial hierarchies in many of its colonies, played a pivotal role in shaping the contours of the global color line and impelled local actors to engage with and position themselves forth it. Nonetheless, indigenous Palestinians and their Zionist settler counterparts (who arrived in the country offset in the late nineteenth century) too drew upon contained reservoirs of racial thought. Since the late nineteenth century, Ottoman and Arab intellectuals and social scientists had engaged with mostly European racial thought. Their interpretations and adaptations of these theories were also shaped by local histories of conquest and enslavement. Ussama Makdisi has shown how Ottoman intellectuals in the tardily nineteenth century developed a soapbox of difference that Makdisi calls "Ottoman Orientalism," which reproduced Western colonial notions of hierarchy and departure between Ottoman Turks and members of other ethnic and national groups within the empire. Racial thinking, inflected by globally circulating notions of race'southward significance, drove the Turkish nationalist quest for "whiteness" during Turkey'south early republican menses and too shaped the contours and legacies of the Greek-Turkish population exchange of 1923, equally Murat Ergin and Aslı Iğsız demonstrate.[3]

Meantime with the rise of Ottoman Orientalism, Arab intellectuals in Egypt and the Levant besides engaged with gimmicky European racial thought. Some, like the Egypt-based Syrian intellectual Muhammad Kurd 'Ali, editor of the journal al-Muqtabas, vehemently rejected the thought of a racial hierarchy of humanity. Others, perhaps most famously Jurji Zaydan—another Syrian intellectual who published the journal al-Hilal in Cairo and was a towering figure of the Arab intellectual awakening known equally the nahda—adopted and adapted European-derived hierarchies, only to identify Arabs (alongside Europeans and Jews) at the highest rung. Ottoman Orientalism and afterwards Turkish claims to whiteness were shaped in function by a perception of Turkish historical dominance and primacy within the empire and in part by notions of so-chosen social improvement projects intended to uplift lesser ethnic groups. Arab claims to whiteness or racial and civilizational superiority, in turn, were frequently framed confronting a history of engagement with the Black of sub-Saharan Africa (and to an extent also Berber North Africa), notions of social improvement of elements within Arab society portrayed as backward and contemporary colonial projects such as Egyptian rule in the Sudan.[iv]

At the same time, a considerable body of Zionist idea, primarily from Eastern and Central Europe, sought to respond to the diverse strands of European racial idea and antisemitism, though oft adopting and adapting bones tenets of those same ideologies. Some Jewish thinkers, including Zionist thinkers, adopted both the idea of Jewish racial degeneracy, which they applied primarily to so-called backward Eastern European Jews, and the remedies of racial nationalisms. The idea of creating a "New Jew," who would be antithetical to the weak, degenerate Eastern European Jew through physical cocky-comeback and regenerate the Jewish nation, was central to the thinking of Zionist intellectuals and leaders like Theodor Herzl and Max Nordau and became a mutual trope among early on Zionists from across the political spectrum.[5]

Experiences of immigration and participation in the work of empire also informed Palestinian and Zionist racial perceptions. Beginning in the tardily nineteenth century, big waves of Arab immigrants from Greater Syria and Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe arrived in places where the "new religion of whiteness"—a term Du Bois coined in 1920—reigned.[six] Primary among these were the Americas. There, aslope other immigrant communities, many Jews and Arabs strove to be identified every bit racially white to achieve a caste of social integration and up mobility.[7] Involvement in Europe'southward colonial enterprises, specially in Africa, whether in official capacities or as migrants in colonial society, was some other avenue through which some Jews and Arabs were able to lay claim to whiteness. The narratives of Lebanese migrants to French colonies in West Africa, Palestinians serving in the Sudan Medical Service and views expressed by Zionists similar Herzl and Israel Zangwill about the whitening propensity of Jewish involvement in colonization demonstrate that, as in the Americas, to get white Jews and Arabs required the presence of other populations considered irretrievably non-white. It was through comparison to the latter that white society and colonial administrations could regard Arabs and Jews as whiter than-, if still not wholly white.[viii] Family unit and customs networks, returning immigrants and newspaper reports "from the diaspora" in Palestine's Arabic and Hebrew press during the early twentieth century carried these understandings of race back to Palestine.

The question of whiteness and racial hierarchies were not all that preoccupied Arab and Jewish intellectuals who turned to racial thought during the belatedly nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For some, racial thought pointed to the connections, even the potential unity, between Jews and Arabs every bit "Semitic" peoples.

The question of whiteness and racial hierarchies were not all that preoccupied Arab and Jewish intellectuals who turned to racial thought during the tardily nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For some, including Jurji Zaydan, racial idea pointed to the connections, even the potential unity, betwixt Jews and Arabs equally "Semitic" peoples. Mayhap unsurprisingly, the notion of Semitic unity fell from grace, peculiarly among Arab intellectuals, as the threat of Zionism and the support information technology received from the groovy powers grew clearer in the menses between the two world wars. Semitic identity, whether viewed as shared by Jews and Arabs or non, operated for some Zionist thinkers alongside myths that traced the origins of the Palestinian fellahin (peasants) to the biblical Hebrews. Semitic identity was as well used to agree up local Palestinian Jews, whose families had lived in Palestine as Ottoman Jews for generations, as proof that Jews were in fact native to the land and non foreign colonizers.[9]

Crucially, interest among Zionists and Palestinians in the role of race as a fashion of ordering the world besides extended beyond questions of self-perception and identification. Outset in the late 1920s and into World State of war Two, Standard arabic and Hebrew language newspapers, such every bit the two major Arabic dailies Filastin and al-Difa', the Hebrew daily Davar, affiliated with the mainstream of Labor Zionism, and more right-wing outlets such equally Do'ar ha-Yom and ha-Boker, were preoccupied with the color line as a theme of global politics. Depending on the ideological proclivities of the newspaper and author, coverage in Hebrew and Arabic affirmed or debunked the concepts of the "yellow threat" and "white refuse," railed against the discrimination of Black Americans in the U.s.a., decried the brutal colonization of Africa or the brutality of African "savages" and discussed the claim and pitfalls of the White Australia immigration policy.

These various lineages guaranteed that ideas well-nigh the links betwixt race, nation, civilization and the body thus circulated in both Palestinian and Zionist circles. The implications of their circulation inverse significantly, nevertheless, when the colonial human relationship and national competition between Zionists and Palestinians came into starker relief. Underlying these preoccupations were 2 questions: where, in a world divided and stratified by race, did each of Palestine'due south political and social communities vest? And what did that mean for Palestine's present and future?

Palestine in Black and White

Casting Zionism as office of European colonialism—and consequently linking it to notions of racial hierarchy—was an appealing suggestion for early Zionist thinkers such as Herzl and Zangwill. But the largely Eastern European Labor Zionists had a considerably more conflicted relationship to Zionism's colonial nature. Labor Zionists' blend of nationalist and socialist thought was embraced by many amidst the 2nd wave of Zionist clearing to Palestine in the early on 1900s and they became the dominant force inside Zionist politics and institutions in the early on 1930s. Upon arrival, these settlers criticized the enterprises of their predecessors who largely relied on local Palestinian labor. They accused them of recreating exploitative colonial labor regimes through a plantation economy in which "native" laborers were lorded over by plantation owners. This do, they argued, went against the socialist principles that inspired them and which, accordingly, set them apart from their predecessors.

Every bit Labor Zionism gradually emerged equally the dominant strength in Zionist politics in subsequent decades, nevertheless, efforts by its leaders to improve the employment atmospheric condition and wages of Palestinian workers were desultory at all-time. Instead, Labor Zionists turned to what they termed the conquest of labor, seeking to guarantee jobs for Jewish immigrants in Jewish enterprises at the expense of Palestinian Arabs.

Labor Zionists turned to what they termed the conquest of labor, seeking to guarantee jobs for Jewish immigrants in Jewish enterprises at the expense of Palestinian Arabs.

Drawing upon the ideas of the new Jew and the connectedness between national rejuvenation and the individual body, they portrayed labor in Palestine every bit a ways of physical and spiritual self-improvement and a necessary footstep in the rebirth of the Hebrew nation. At the same fourth dimension, they likewise demanded that European Jewish immigrants receive significantly higher wages than their Arab counterparts for equal piece of work. They justified this need on account of Jewish immigrant'south supposedly higher standard of living. That is, the higher costs (and, whether implicitly or explicitly, also the greater refinement) of maintaining the diets, livings weather condition and recreational activities they were accustomed to. Historians of the standard of living elsewhere, it should be noted, have shown that as a metric the standard of living itself was embedded in concepts of physiological and cultural differences, often mapped onto race.[ten]

The conquest of labor in line with socialist principles led to pregnant segregation in Palestine'southward workforce. Offset in the 1920s, some Jewish-owned industrial undertakings—where the struggle to employ exclusively Jewish labor proved at first impossible—were instead segregated internally forth racial lines. Typically, this meant that European Jewish immigrants were employed in higher paying, skilled jobs, while Palestinian Arabs (and sometimes Mizrahi Jews) were employed in lower paying and physically enervating, and then-chosen unskilled labor.

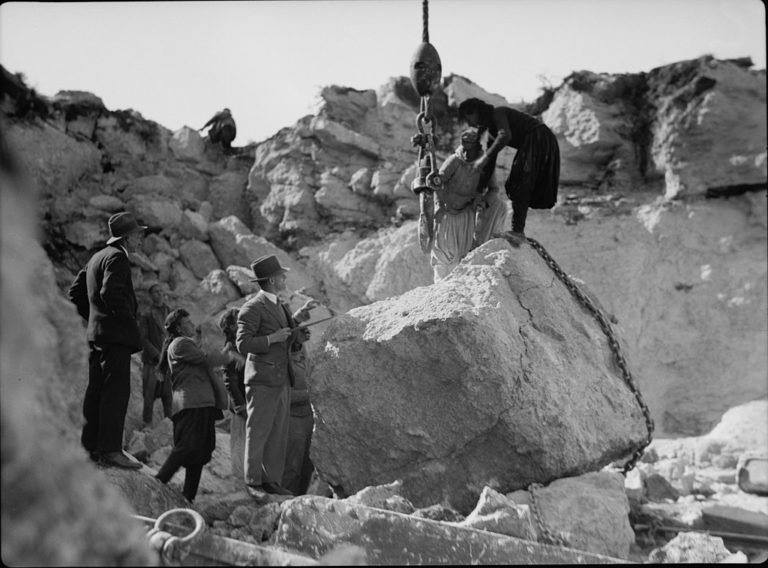

Workers in the Athlit quarry during the construction of the Haifa harbor in the 1920s where the British proposed dividing Arab and Jewish workers into different skill categories along racial lines. Library of Congress, G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection.

A similar arroyo was considered past the British administration when planning its showtime major infrastructural undertaking in Palestine—building the Haifa deep-h2o harbor in 1928. In the face of demands past the General Federation of Merchandise Unions (Histadrut), the most of import organ of Labor Zionism, to pay Jewish workers employed in the harbor'due south construction higher wages than their Arab peers, the British devised a solution linking race to skill. In accordance with what they perceived as each race's natural tendencies, Jews—a category that for the British appears to have included merely European Jews and excluded Mizrahim—would work in college paying, more than technically enervating positions, while Arabs would exist directed toward lower paid physical labor. "The rivalry between the Jews and Arabs [in the matter of the sectionalization of labor and wage inequality]," was "mitigated by the fact that the two races tend to go naturally segregated in different kinds of labor," wrote then High Commissioner John Chancellor. He clarified, "the Jews gravitate to skilled and semi-skilled labour, which requires intelligence and initiative, and the Arabs to heavy unskilled labour for which by reason of their superior physique they are better fitted."[eleven]

The crude racial binary between Arabs and Jews that the British adopted in the case of the Haifa harbor construction, and that guided much of British policy making during the Mandate period, erased not only Mizrahi Jews. As racial thought invariably does, it collapsed the variety within the groups information technology supposedly represented into monolithic, discrete fictions. The erasure of the Mizrahim, here and elsewhere, is specially notable still, because of their liminal position betwixt the two monolithic categories. Mizrahim itself is a classification which erases internal social, cultural, economic and other forms of diversity. For example, the Sephardi elite of Jerusalem shared relatively little in common with recent Yemeni immigrants to the same metropolis, who in turn had quite different life experiences from Northward African or Kurdish Jews. As numerous scholars accept demonstrated, most communities commonly grouped under this heading (and to an extent, likewise members of Palestine's established Ashkenazi communities) could potentially span the perceived Arab-Jewish and Eye Eastern-European binaries and chance muddying the categories that made those binaries possible. Whether or non diverse actors, including Mizrahim themselves, embraced or rejected these potentialities, depended on the context. The "Palestinian Jew" was a useful category for Zionists who wanted to merits Palestinian nativeness. But the Sephardi elite, through which this nativeness could be claimed, was at the same fourth dimension sidelined by various Zionist institutions during the British Mandate and denied the role information technology held for centuries under the Ottomans as representative of Palestine's Jewish population. Yemeni Jews were held up every bit exemplars of "authentic" Jewishness and meantime considered a reliable source of cheap, docile labor.

Every bit the Zionist and Palestinian national movements crystalized and the stakes of Zionist colonization in Palestine nether the aegis of the British Mandate grew clearer, the boundaries between "Jew" and "Arab" hardened.

Every bit the Zionist and Palestinian national movements crystalized and the stakes of Zionist colonization in Palestine under the aegis of the British Mandate grew clearer, the boundaries betwixt "Jew" and "Arab" hardened. The position of the Arab Jew became more fraught simply besides, as several generations of Mizrahi scholars and activists have insisted, all the more of import and fruitful. It appears that the British erasure of Mizrahi Jews from the racial sectionalization of labor they proposed at the Haifa harbor in 1928 was not a result of perceiving European Jewish settlers and Mizrahi Jews equally indistinguishable. Rather, information technology was because every bit time wore on, they came to see the Mizrahim every bit politically inconsequential. For the mandate authorities, European Zionists represented, perhaps even constituted, the Jewish "nation" that the British were beholden to by the Balfour declaration.[12]

Zionist institutions—including the Histadrut and the Zionist Executive, the umbrella organization that represented many Zionist parties in Palestine—rejected the British suggestion for dividing labor at the Haifa harbor. In doing and so they cited their opposition to a colonial sectionalisation of labor and their ambitions to identify Jewish workers in every branch of the economy. By the time the argue arose, notwithstanding, the concept of the global colour line was already furnishing Palestinian opposition to Zionism with the linguistic communication of anti-racism and feeding Zionist anxieties about the movement's colonial underpinnings. For example, an article in the Palestinian daily Filastin on Oct nine, 1928, past an unnamed author charged that Zionist demands for higher wages and a greater share of jobs for Jews in the Haifa harbor and elsewhere, equally well as the language of the standard of living more broadly, rested upon an assumption of white civilizational refinement supposedly shared by European Jews and the British. In belatedly January 1929, the English language-linguistic communication Zionist newspaper The New Palestine published an article expressing hope that the appointment of John Chancellor, formerly governor of Rhodesia, to the office of High Commissioner for Palestine would mean increased British support of Zionist settlement efforts, equal to their support provided to white settlers in the African colonies. On Feb 1, a response piece in Filastin, unsigned once over again, pointed out that this too was an appeal to a racial world order. If the logic of empire were to determine Palestine'southward future, both pieces seemed to contend, Zionist Jews were its white settlers and Palestinians its Black natives. It was to this logic that Zionists, despite their equivocations and refutations, appealed when demanding preferential treatment, the articles unsaid. It was this logic that Palestinians needed to resist.

The global colour line provided other frames of reference as well. The figure of the "coolie" and coolie labor were frequently invoked past Labor Zionists as characteristic of the evils of empire and the British empire in particular.[13] Coolie is a term that during the nineteenth century was associated with by and large Asian, exploited and denigrated migrant laborers both in the British empire and in the U.s.a.. Historian Moon Ho-Jung has described the term as "[neither] a people [north]or a legal category….Merely a conglomeration of racial imaginings." In tandem, some critics suggested that such racial regimes of labor were also making inroads into Jewish lodge in Palestine and employed the term coolie to warn specifically of the attitudes of politicians and employers to Mizrahi Jews. For example, in mid-1929 Benzion Mossinson of the liberal General Zionists party, warned in the party'southward general assembly of a "politics of coolies" that sought to encourage Mizrahi Jewish clearing to Palestine so that they could serve as cheap labor. This scenario was inappreciably an unthinkable outcome. In 1911, Arthur Ruppin—the head of the Palestine Office, an of import instrument of Zionist colonization—along with members of the planter class that took root in Palestine during the first wave of Zionist migration in the belatedly nineteenth century, had infamously initiated a mission to encourage the immigration of Yemeni Jews to Palestine. They hailed the Yemenis equally appropriately Hebrew but also adequately cheap "natural workers," by virtue of their physiology and civilisation, who could compete with Palestinians for like jobs and wages.

By the 1940s, striking Mizrahi workers and Mizrahi newspapers invoked the figure of the coolie to depict both the intentions of Labor Zionist institutions toward them and already existing divisions of labor. When a group made up of largely Mizrahi workers from a quarry outside Haifa, partly endemic by the Histadrut, went on strike in November 1940, their protests—led past the workers' wives—included issuing a pamphlet that cited their refusal to be "relegated to the level of coolies." A 1944 article responding to a Histadrut report on Jewish workers in Jerusalem and published in Hed ha-Mizrah, a newspaper affiliated with the Sephardic community in Jerusalem, decried the transformation of the city's Mizrahi Jews into a "population of Jewish coolies."

Labor Zionist leaders, in particular, repeatedly reasserted the motility's opposition to these vestiges of race and imperialism and sought to muffle instances that might generate the impression they were in fact role and parcel of the Zionist enterprise.

These manifestations of the colonial racial gild in Palestine undermined Zionist self-perceptions and self-presentation. Labor Zionist leaders, in particular, repeatedly reasserted the move's opposition to these vestiges of race and imperialism and sought to conceal instances that might generate the impression they were in fact part and bundle of the Zionist enterprise. Some fifty-fifty issued warnings of their dangers to the Zionist project. But no thing how hard they tried to altitude the Zionist project from race and imperialism, the movement remains haunted by them ideologically because its project has ever been divers by them in practice.

It is possibly fitting that one of the most reviled manifestations of the color line in the twentieth century, apartheid South Africa, remains one of Zionism's most consistent demons to the present day. Indeed, even prior to the institutionalization of apartheid and Israel's establishment, both in 1948, Due south Africa's racial regime loomed large in the thinking of some Zionist figures. Apartheid'southward legal forebearer, the Due south African "color bar," that dictated which racial groups were allowed to work in which industries and positions, was invoked by Zionist leaders as an of import, if improbable, model for addressing questions of labor and economic system in Palestine. At central moments—from the 1927 writings of Labor Zionist thinker Hayyim Arlosoroff to the eve-of-independence 1947 plans for the new Jewish state'south Department of Labor authored by economist Alfred Bonne—the South African model emerged as the closest equivalent to the challenges facing Zionist settlement and state-edifice.[14] Both Arlosoroff and Bonne alluded to the moral questions surrounding the South African model—Bonne more than explicitly so. Simply for both, information technology was the geopolitical impracticality of emulating the model that ultimately ruled information technology out.

The Long Twentieth Century

The colour line remained close at hand afterward the state of war of 1948—the Palestinian Nakba and State of israel's independence. In its first decade, the Israeli state contended with what Shira Robinson has called its "colonial specter"—the inescapable association with colonial racism in a fourth dimension of burgeoning anti-colonial nationalisms.[fifteen] It was not a specter because information technology was somehow unreal but precisely because actual Israeli policies and Zionism'due south evolution meant that no affair how hard they tried, Israeli officials could not avoid information technology. Marginalized Palestinian citizens and Mizrahi Jews in the nascent land continued to deploy the oppositional language binding together racism, empire and colonialism. Such opposition and solidarity were carried forth by, amidst others, the increasingly influential Communist Party amid Palestinians and by the various groups that participated in the Mizrahi social and political struggles of the period. The most well-known, and arguably the most explicit, instance of tying anti-discrimination struggles in Israel to struggles elsewhere through such an idiom, was that of the Mizrahi-led Blackness Panthers movement. It was established in 1971 by Mizrahi youth from the Musrara neighborhood in Jerusalem to combat institutional discrimination and fail of Mizrahi Jews inside Israel. The movement non merely adopted the name and visual language of the US-based Black Panthers movement, only likewise actively sought connections with it. Earlier, lesser-known struggles besides appealed to such global idioms, such as when the Palestinians of the Shaghur Valley in northern State of israel protested confronting the seizure of their quarries by the state in the mid-1950s. In a letter sent to the Israeli president and to the British and American consulates they described a "chain of racial persecution" unleashed by the country and stated that British colonial rule was preferable to Israel'south so-chosen democracy. Bryan Roby too documents multiple instances of such appeals by Mizrahi Jews in Israel prior to the rise of the Black Panthers.[16]

The about well-known, and arguably the most explicit, example of tying anti-discrimination struggles in State of israel to struggles elsewhere through such an idiom, was that of the Mizrahi-led Black Panthers movement.

Palestine became intimately linked to anti-regal and anti-colonial politics, especially later the war of 1967. However, while it was under Ottoman rule until 1917 and and so British rule until 1948, it was by no means a key site along the colour line. The theaters of the struggle for global racial equality appeared to be concentrated elsewhere—in the Americas, the Pacific, South Asia, Oceania and Sub-Saharan Africa. Palestinians of all faiths and Zionist settlers were, for the most role, marginal in this racial world order at least until National Socialism and the Holocaust redefined it. Notwithstanding, the color line and its logic exerted their gravitational pull on the state and its populations, demonstrating the affectibility of Du Bois' 1903 diagnosis and the magnitude of "the trouble of the twentieth century."

Analyzing the workings of the colour line in Palestine and Israel and mapping the trajectories through which race and racialization came to play a fundamental role in the state, illuminate the truly global achieve of its logic and highlight some of the backdrop that have made the global color line so durable. Over the past several decades, scholars of race and anti-racist activists—especially those attentive to racism's global dynamics and political economic dimensions—have highlighted the color line's endurance into the twenty-commencement century. The global affect of the Blackness Lives Thing movement in 2020, on the 1 hand, and the injustices and inequalities laid bare by the COVID-nineteen pandemic plus the climate crisis and the global resurgence of white supremacy and right-wing populist nationalism, on the other, indicate that indeed the trouble Du Bois identified over i hundred years ago remains a defining feature of the present.

The contours of racial politics in Palestine and Israel throw seemingly contradictory aspects of the color line's immovability into stark relief. Its concrete connections to and bear on on political economy and the torso that are captured in the ongoing links between race and divisions of labor and course are one aspect. Another is the color line's mutability and tenuousness as seen in the capacity of supposedly stable racial groups to concurrently position themselves differently in different settings, equally a product of their relationship to power. There are other instances that demonstrate this flexibility, including the experiences of Jewish and Palestinian immigrants in the Americas and Africa. But none are more potent than the way that the color line in Palestine and State of israel cast European Jews as the proponents and beneficiaries of a colonial racial order at the same time that Nazi credo rendered them as the white race's ultimate racial other. Du Bois himself came to expand his understanding of race every bit a global force following his visit to the remnants of the Warsaw ghetto in the aftermath of World War II. Information technology was at that place that Du Bois realized that "the race problem in which I was interested cut across lines of colour and physique," and emerged "into a broader conception of what the fight against race segregation, religious discrimination and the oppression by wealth had to become if culture was going to triumph and broaden in the world."[17]

[Nimrod Ben Zeev is a fellow at the Polonsky Academy for Avant-garde Report in the Humanities and Social Sciences at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute.]

Endnotes

[one] Alex Lubin, Geographies of Liberation: The Making of an Afro-Arab Political Imaginary (Chapel Colina: University of North Carolina Printing, 2014); Keith Feldman, A Shadow over Palestine: The Imperial Life of Race in America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015); Michael R. Fischbach, Black Ability and Palestine: Transnational Countries of Color (Stanford: Stanford Academy Press, 2019); Noura Erekat and Marc Lamont Colina, eds., "Black Palestinian Transnational Solidarity." Special outcome, Journal of Palestine Studies 48/four (Summer 2019).

[2] West. East. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (New Haven: Yale University Printing, 2015 [1903]); Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds, Drawing the Global Colour Line: White Men'due south Countries and the International Claiming of Racial Equality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

[3] Ussama Makdisi, "Ottoman Orientalism," The American Historical Review 107/3 (June 2002); Murat Ergin, "Is the Turk a White Human being?": Race and Modernity in the Making of Turkish Identity, "Is the Turk a White Man?" (Leiden: Brill, 2016); Aslı Iğsız, Humanism in Ruins: Entangled Legacies of the Greek-Turkish Population Exchange (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018).

[4] Eve Troutt Powell, A Different Shade of Colonialism: Arab republic of egypt, Great Britain, and the Mastery of the Sudan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003); Omnia El Shakry, The Great Social Laboratory: Subjects of Noesis in Colonial and Postcolonial Egypt (Stanford: Stanford Academy Press, 2007); Sarah M. A. Gualtieri, Betwixt Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009).

[5] Todd Samuel Presner, Muscular Judaism: The Jewish Torso and the Politics of Regeneration (London: Routledge, 2007); Nadia Abu El-Haj, The Genealogical Scientific discipline the Search for Jewish Origins and the Politics of Epistemology (Chicago: The Academy of Chicago Press, 2012).

[6] Due west. E. B Du Bois, Darkwater: Voices from within the Veil (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1999 [1920]).

[7] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White…; Eric L. Goldstein, The Toll of Whiteness: Jews, Race, and American Identity (Princeton: Princeton Academy Press, 2008); Camila Pastor, The Mexican Mahjar: Transnational Maronites, Jews, and Arabs under the French Mandate (Austin: Academy of Texas Press, 2017).

[8] Eitan Bar-Yosef and Nadia Valman, eds. 'The Jew' in Late-Victorian and Edwardian Civilisation: Between the East End and Eastward Africa (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Sherene Seikaly, "The Matter of Time," The American Historical Review 124/5 (2019).

[nine] Jonathan Marc Gribetz, Defining Neighbors: Organized religion, Race, and the Early Zionist-Arab Encounter (Princeton: Princeton Academy Press, 2014); Orit Bashkin, "The Colonized Semites and the Infectious disease: Theorizing and Narrativizing Anti-Semitism in the Levant, 1870–1914," Disquisitional Inquiry 47/two (2020).

[ten] Lawrence Glickman, "Inventing the 'American Standard of Living': Gender, Race and Working-Class Identity, 1880–1925," Labor History 34/2–iii (June 1993).

[11] The National Archives (Britain), Colonial Office (CO) 733/165/two.

[12] Tim Sontheimer, "Bringing the British back in: Sephardim, Ashkenazi anti-Zionist Orthodox and the policy of Jewish Unity," Middle Eastern Studies 52/ii (2016).

[xiii] Moon-Ho Jung, Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Saccharide in the Age of Emancipation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009).

[xiv] Zachary Lockman, "Country, Labor and the Logic of Zionism: A Critical Engagement with Gershon Shafir," Settler Colonial Studies two/one (January 2012). Alfred Bonne, "The Trouble of Arab Labour within the New Jewish State," State of israel State Archives, ISA-no-no-0007e6x.

[15] Shira Robinson, Citizen Strangers: Palestinians and the Birth of State of israel's Liberal Settler State (Stanford: Stanford Academy Printing, 2013).

[sixteen] Letter from residents of Nahf to the Counselor on Arab Affairs in the Prime Minister's Office, August 1, 1952, Israel State Archives, ISA-PMO-ArabAffairsAdvisor-000fq6j; Bryan K. Roby, The Mizrahi Era of Rebellion: Israel'due south Forgotten Ceremonious Rights Struggle 1948-1966 (Syracuse: Syracuse Academy Press, 2015).

[17] W.E.B. Du Bois, "The Negro and the Warsaw Ghetto," Jewish Life vi/7 (May 1952).

phillipspreempory.blogspot.com

Source: https://merip.org/2021/08/tracing-the-historical-relevance-of-race-in-palestine-and-israel/

0 Response to "Review Communism and Zionism in Palestine During the British Mandate Shira Robinson"

Post a Comment